Susannah Cremer-Bermbach 2021

Cum Cera

The sculptures and paper works of art by Barbara Deutschmann

“... But form is also something that is often carved into experiences, exposing something with which you forget the finite: an oblivion taken for beauty.” 1

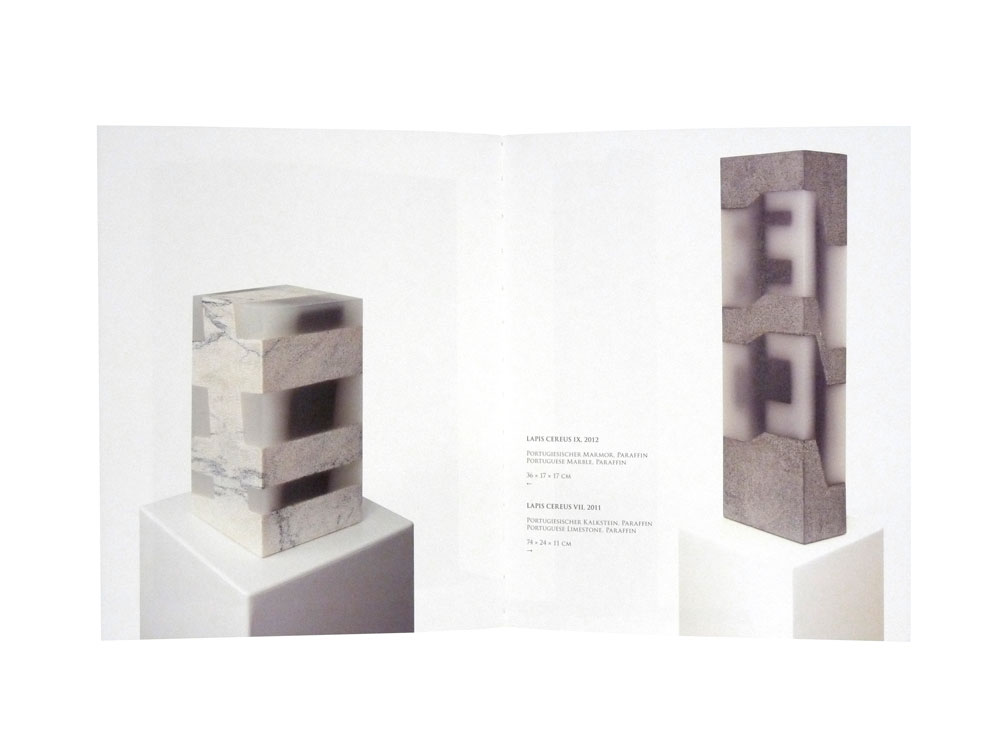

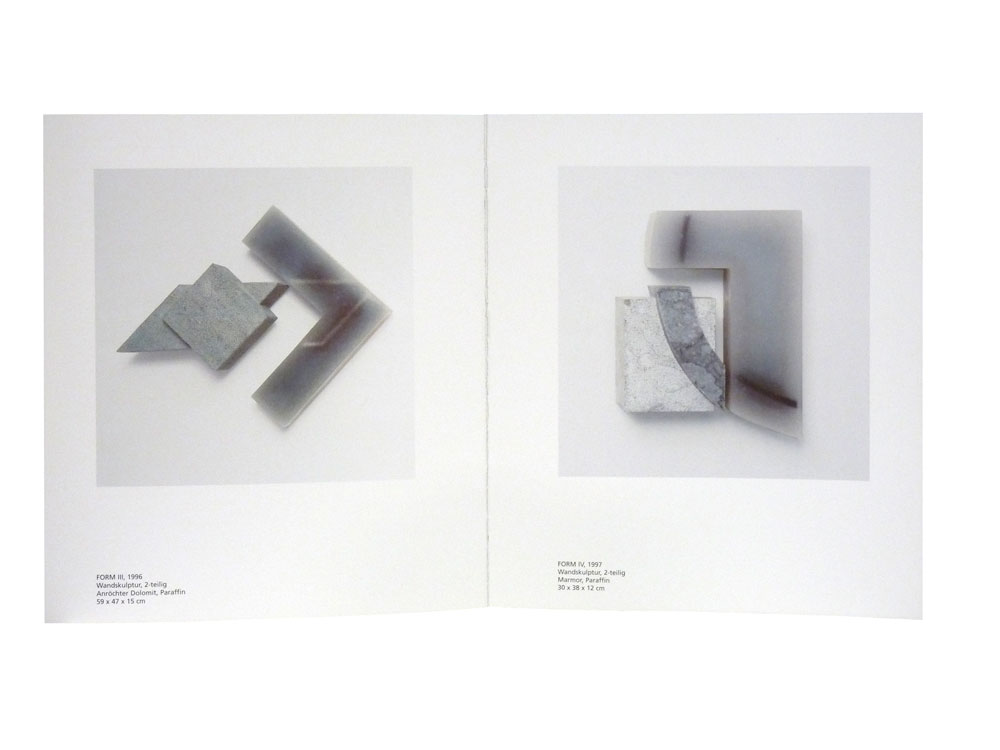

The sculptures present themselves initially as geometrical shapes made of contrasting materials: the concrete or stone is hard, heavy, opaque, the wax is relatively soft and, due to its translucency, apparently lightweight. At a second glance the technical process also seems contrasting: resistant and durable material carved or cut into shape, and material whose texture depends on temperature, moulded into shape–a sculptural and a plastic process, each having a long tradition, joined together in one work of art. Inbetween is the awareness of another contrast: geometrical shapes and lines which are clearly and precisely contoured on the outside, appear blurred inside the wax forms. This insight in an interior marked by linear shapes, which, like a shadow room, cannot be identified clearly despite the outer clarity, is the actual event.

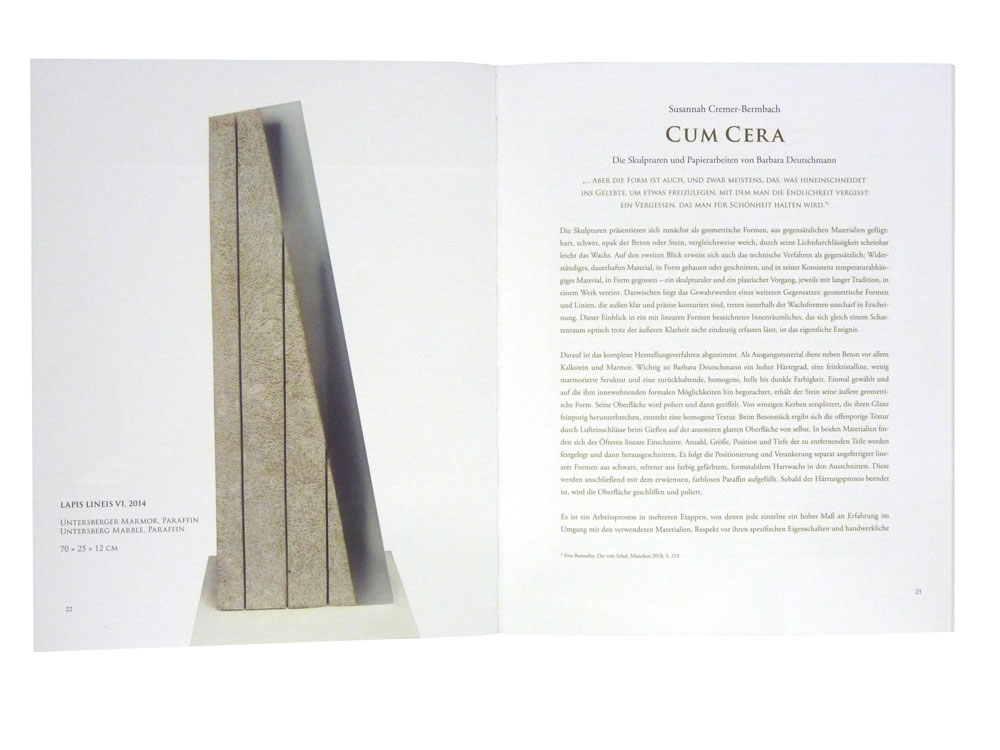

The complex manufacturing process attunes to this. In addition to concrete, limestone and marble in particular serve as raw materials. Important for Barbara Deutschmann is a high degree of hardness, a fine crystalline, sparsely marbled structure and a subtle, homogeneous, light to dark colour. Once chosen and examined in terms of its immanent formal possibilities, the stone gets its external geometrical shape. The surface is initially smoothed and later carved to show chisel marks. A homogenous texture is created by tiny undercuts that break down the glossy structure. The concrete part has a typical pored texture, caused naturally by trapped air during casting. Linear fissures are visible in both materials. Amount, position, and depth of the parts that are to be removed are determined and then cut out. This is followed by the positioning and mounting of separately made linear shapes of black or sometimes also coloured stable hard wax in the cutouts. These are then filled with heated, colourless paraffin. As soon as the hardening process is over, the surface is sanded and polished.

It is a work process with different stages of which each single one demands a high degree of experience in handling the materials, respect for their specific characteristics and craftsmanship. The same applies to the works on paper that are created independent of the sculptures, although work stages are less elaborate and complex and can therefore be done more directly. Invariably, strong, but not too hard, absorbent paper with a prominent structure is used as a basis: preferably long-fibred and irregularly structured handmade hemp or Himalaya paper, sometimes relatively evenly structured paper like deckle edge. First of all, rectangular areas of colourless paraffin are created with an encaustic pen on the front, some distorted in their perspective and divided by linear spaces; similar areas and thin lines of black coloured paraffin are applied on the back. Afterwards black areas visible on the front are reprocessed with black wax. This leads to an interaction between opaque and transparent, precisely contoured and blurred lines and areas, between statics and dynamics. The constructive appearance is playfully infiltrated by shifts and interleaving that seem plausible at first but then turn out to be more or less contradictory.

Fixed with a spacer in the middle of the background of the frame, the paper object develops its own, real physical presence accentuated by ripples and bulges, independent of the irritating concept of space.

As a stone sculptor, Barbara Deutschmann is aware of the long history of this art genre which goes back to the 19th century and is inspired by the Greek and Roman antiquity. She also knows how wax was used traditionally and that it was not regarded as having an own artistic quality in ancient times. In art painting it had been an essential ingredient for binding colour pigments which were mixed with the hot wax and melted together with the image carrier during the encaustic procedure. Encaustic was used for portraits of mummies and later for early Christian icons. Wax had an important role as model and mould when making sculptures and plastics, especially death masks. The Romans also used it to even out imperfections in their figures. With a few exceptions, the main visible use of wax until the 20th century was in the decorative arts in such wide variations from wax figures and doll heads via anatomical specimens and moulage casting to devotional pictures and votive gifts. Today the use of wax is mainly limited to candles.

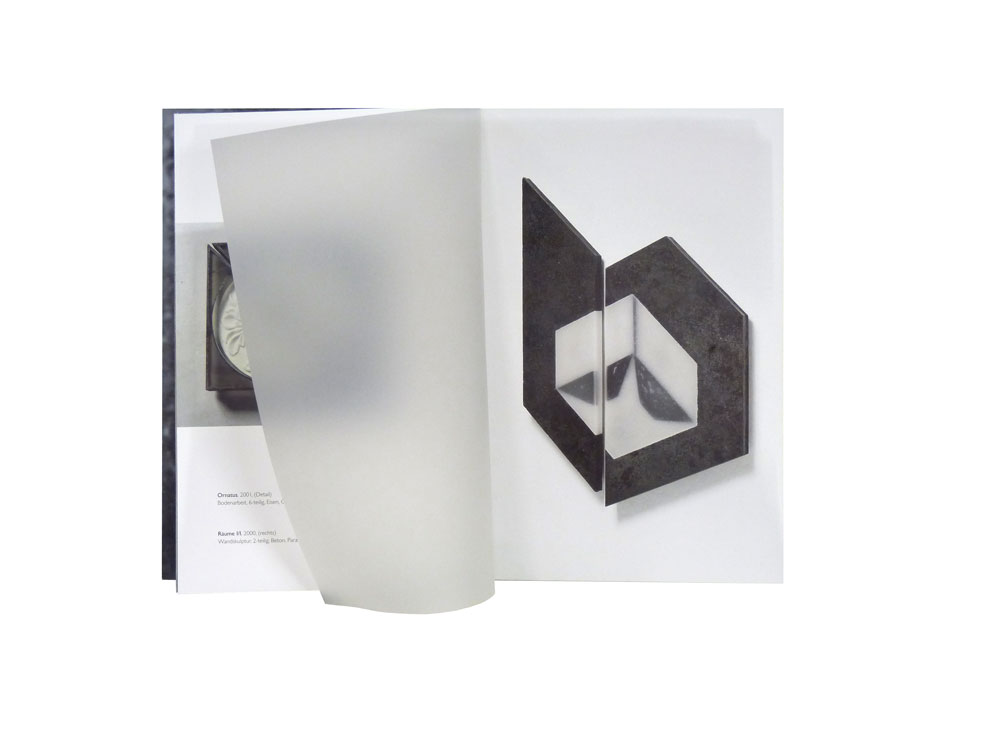

During her training as a stage sculptor at the National Theatre in Mannheim and her studies at the University of the Arts in Bremen in the 1980s, she focused on figurative and abstract forms. At that time she also began to work with stone, concrete, wax and cast resin. When she became a freelance artist in 1992 she concentrated exclusively on these materials and geometrical artistic forms. In the 1990s she first created assembled wall sculptures in which cast concrete parts and monochrome or polychrome parts made with paraffin enter into a dialogue. These sculptures already represent her interaction with statics and dynamics, tranquility and motion, with the rhythms of motion and contrary motion. So she already employed techniques like casting wax into concrete and integrating linear forms of hard wax into paraffin in her early works.

Assembled wall sculptures were Barbara Deutschmann s preferred style for many years. Increasing struggles with walls as boundaries, as limitations in space, led to the physical and spatial autonomy of freestanding sculptures which can be looked at from all angles and thus include the element of motion. Experiences gained here also enabled a new view on surfaces which she explores in her paper works. Barbara Deutschmann occasionally checks her ability to observe precisely and to take correct measurements by eye through drawing figures and objects. These private “finger exercises” are barely worth talking about but

they are part of an art-historical background that seems to shine through her sculptures. Her Latin titles reflect this with casual sovereignty. It appears even more succinct and pointed in the catalogue‘s title. The name “SINE CERA” was a sign of quality in ancient Rome for a perfectly crafted sculpture which did not need any further addition of wax. In turn “CUM CERA” refers tongue-in-cheek to a technically similar but in its intention diametrically opposed approach: the stone is carefully fragmented and the missing parts are shaped with wax to a plastic volume according to the outer contours. Both materials, the sculptured as well as the plastically formed, are autonomous and treated equally and at the same time relate to each other in a contrasting way.

Her clear, geometrical and harmonious artistic form puts her sculptures and paper works in the same line as concrete art whose aim was to create works for “mental purposes” according to Max Bill in 1947. Meant here was a rational i.e. intellectual approach to the arts. The visual sense is supposed to be addressed and developed as a “reflecting” eye. Barbara Deutschmann‘s sculptures do more than this. At first they seduce the eye: besides being able to handle materials like stone, concrete or paper and wax according to their natural characteristics, Deutschmann also displays the immanent beauty of the materials. The balanced proportioning of parts and restrained colours radiate calm and silence. The materials and their meticulous treatment stimulate the desire to touch them. The roughened surface lets the stone seem as if it is covered by fine-pored skin and appears therefore almost soft, vulnerable and more warm than cold. The smoothly polished surface of the wax on the other hand appears solid and resilient, more cold than warm. The cast dark forms of hard wax are reminiscent of

containments like fossilised resin. We hardly notice that the optical impression contradicts what we know about the nature of stone and wax. This awakens the desire for haptic confirmation.

The sensual attractivity is enhanced by the semi-transparency of the wax which only allows vague insights into the interior of the sculpture. Depending on the light the embedded linear forms are a horizontal, vertical and diagonal continuation of the lines cut in stone, they connect and complement them. Sometimes they form geometrical bodies. Or they reflect shapes that result from the pieces cut out of the stone. The attempt to distinguish between the real texture and an illusion, between what it is and what it seems to be fails due to the lack of clarity. This failure, in turn, gives the imagination or the “inner eye” (if trained) the opportunity to further shape the space with one‘s own thoughts and memories. So it is about perception that reflects and self-reflects. And this is not so much inspired by what we can clearly see but by a kind of blurriness that we perceive when

looking out of the window in a train. As a projection space for the intellect as well as the psyche it shows us that we always perceive more than what we see.2

The actual topic is neither the geometrical, reduced language of form nor the synthesis of contrasting materials. Essential and common among all groups of works is the irritation building up in the interplay of clarity and blurriness, statics and dynamics, of motion, counter motion and tranquillity – which seems to relocate the spatiotemporal structure with the quasi imploding motion dynamics. That what is achieved in the paperworks by the perspective relocation of lines and surfaces which are sometimes blurred, sometimes clearly contoured and layered on top of one another, is created in the sculptures by the inner life of the wax forms. Their texture makes the contours of the linear forms become softly blurred, as if painted in sfumato technique. We do not find out anything specific, not about their actual formal character and even less about the space in which they are located. The outer shape only allows the conclusion that it must be small. We can measure its height and width visually. What we are unsure about is its depth. It is intensified subtly when the lines cast in wax become a continuation of those cut in stone or concrete. Or intensified even more when the lines join into a geometrical shape in perspective. Thanks to the blurriness of the interior, taken to the absurd as an illusionary space, what remains is the perception of something that emerges as a reflection, shadow, or silhouette of something that is embedded or is a sediment in an interspace, and only completes and fulfills itself beyond the measurability of space and time in a thought, a feeling, a memory, an insight.

1quotation from Yves Bonnefoy, Der rote Schal, München 2018, p.219, freely translated by Sylvia James

2 or further details see: Wolfgang Ullrich, Die Geschichte der Unschärfe, Berlin 2002